Internet Art

- Internet art refers both to a particular art practice, defined by digital media, interactivity, networks and communication, and a particular movement of artists, referred to as net.art, which was most prominent during the early years of the web, or web 1.0.

- In 1995, eight percent of new websites were being made by artists.

- Many of the artists who began practices net art during this period are still practicing, and the Internet is utilized by more and more contemporary artists, but the movement of net.art can more or less be confined to the period between 1991, when the World Wide Web first became available, to around 2001, when the rise of Web 2.0 lead to increased commercialism and homogeny on the web.

Art precedents

Dada is often cited as an earlier art movement influential on Internet art. Dada started in Switzerland in 1916 and spread to Berlin and New York, as well as other cities. Dada was an avant garde movement that embraced non-traditional forms, like graphic design, theatre, theory, manifestos and poetry, as well as new visual styles including collage, assemblage and readymades, and rejected the standards of fine art. It was born out of anti-war and anti-capitalist sentiments during World War I. Much of the work was political and intended to antagonize standards of art and culture. Early Internet art drew inspiration both from the politics and methods of Dadaists.

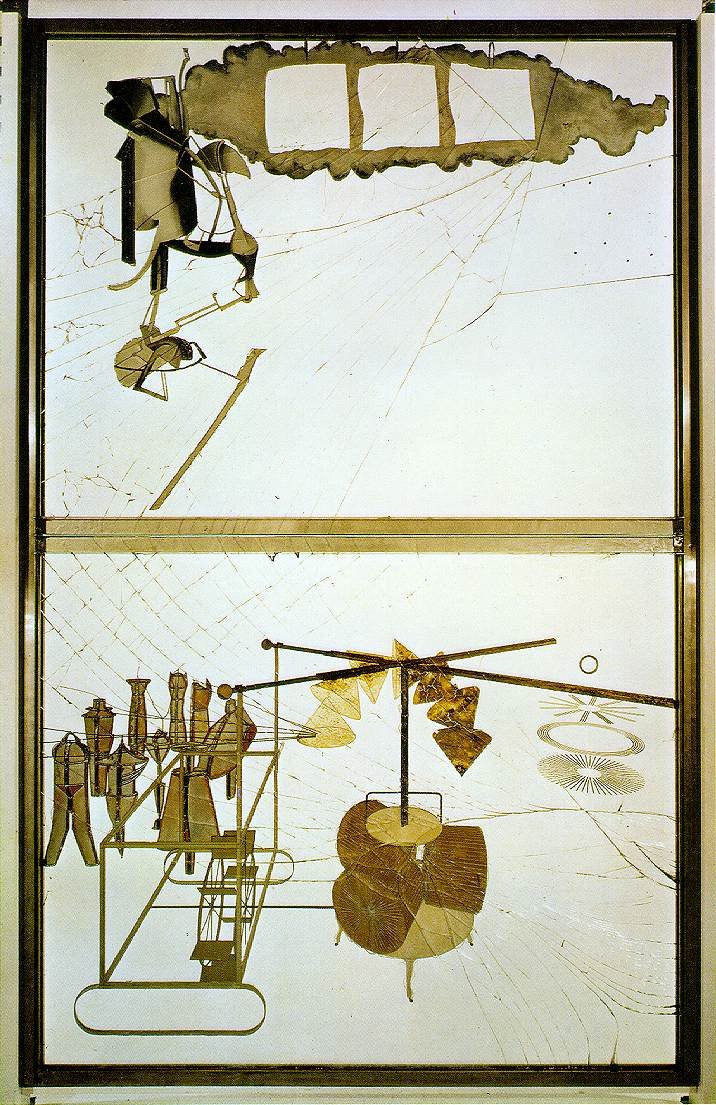

Perhaps the most well known Dadaist is Marcel Duchamp, who is often cited as an inspiration by Internet artists and theorists of Internet art. Duchamp gained notoriety for his rejections of "retinal" work, art made to please the eye, in favor of more intellectual or conceptual work. He first scandalized the art world with his Post-impressionist paintings that were offensive to the tastes at the time, which favored representational work and realism. He became associated with the Dadaists and created more controversy in 1917 when he submitted a "readymade" urinal to an exhibition, which was rejected as "not art". One of Duchamp's works, The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even, provided the inspiration for the title of Marshall McLuhan's first book, The Mechanical Bride, which references the co-existence of sexuality and technology in the work, which McLuhan saw happening in advertising. Duchamp pioneered conceptual art and rejected what he saw as capitalist and aesthetic art, creating a precedent for much of the avant garde of the 20th century.

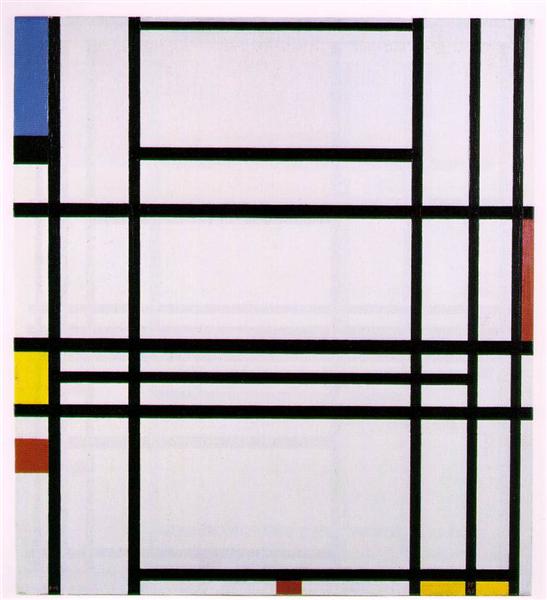

Piet Mondrian, Composition No. 10, (1939-42).

Another important influence of Internet art is formalism, which took up compositional elements as its subject matter, disregarding representational work and the social context of art.

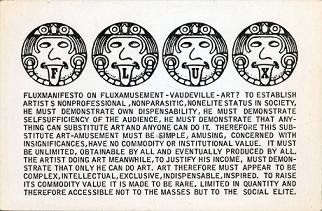

In the 1960s, another art movement characterized by political work, anti-art sentiment and multidisciplinary practice, called Fluxus, which included prominent figures like Nam June Paik, Joseph Beuys and Yoko Ono. The movement grew out of the work and philosophy of John Cage, an experimental composer who became influential in the 1950s. Fluxus was also influenced by Duchamp. Fluxus pioneered a "do it yourself" or amateur aesthetic and an anti-art, anti-capitalist paradigm.

Pre Internet media works

1965: Computer-Generated Pictures exhibition at Howard Weiss Gallery in New York.

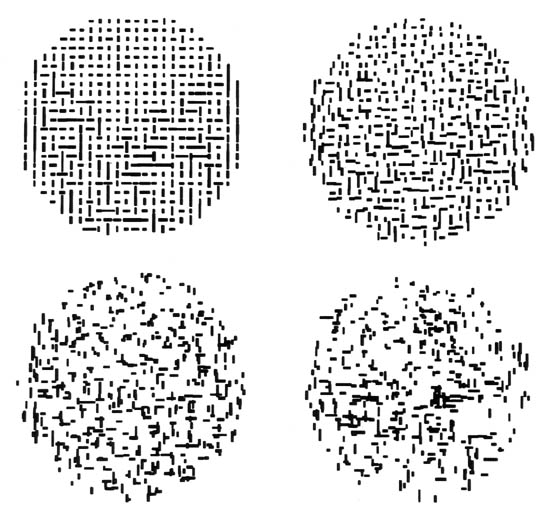

A. Michael Noll, Computer Four Computer-Generated Random Patterns Based on the Composition Criteria Of Mondrian's Composition With Lines, (1964).

1965: Movie-Drome by Stan VanDerBeek anticipates networked video and multimedia, projecting 16 different video sources onto the walls of a geodesic dome.

1966: Billy Kluver, an electrical engineer at Bell Labs, first organizes the Experiments in Art and Technology organization to facilitate collaborations between artists and engineers. Their first event, 9 Evenings: Theatre and Engineering, features work by John Cage, Robert Rauschenberg, Robert Whitman and others.

1968: Nam June Paik published Cybernated Art, in which he describes his approach to work involving television, video and networks. In 1984 he created the work, Good Morning, Mr. Orwell, broadcast via satellite to Germany and South Korea.

1970: Radical Software, an early video art journal that encouraged copying and new methods of distribution.

1974: Vera Frenkel commissioned by Bell Canada to make work involving real-time networked video transmission. Frenkel chose to perform a game of cat's cradle, communicating between two teams based in Toronto and Montreal.

Rehearsal for the video-performance, String Games: Improvisations for Inter-City Video (Montreal–Toronto, 1974).

1979: The first Ars Electronica conference in Linz, Austria. The conference features works, talks and papers about digital art.

1980: After Walker Evans exhibition by Sherrie Levine. The artist photographed famous photos by Walker Evans of rural Americans during the great depression. The works were presented as Levine's own, raising questions about authority and copies that become relevant in the digital age. The work is eventually made into a website and then another site, aftersherrielevine.com with the same material, made by programmer and artist Michael Mandiberg in 2001.

1983: La Plissure du Texte, a work by Roy Ascott made for the Electra 1983 exhibition, a survey of art using electricity, used the ARTEX network to create a world-wide, distributed narrative, which became a collectively written fairytale. The composition lasted 24 hours and resulted in several different versions of the final text.

Original press release for La Plissure du Texte.

Early web artists and net.art

Many of the early works of Internet art are attributed to a small group of practitioners who called themselves net.art or net.artists, an ironic gesture the nomenclature of the web. These works started to appear in 1993 with the rise of graphical web browsers like netscape. These early works often took up the Internet itself as their subject, playing with the form and function of the tools that existed at the time, HTML, browsers, email, message systems and Java plugins. These works mixed collage, sound, text, video, animation and interaction. They formed a community online, one message boards like Nettime and 7-11. There were often disagreements within the small community about what they represented and the meaning of art in general, some working to actively defy interpretation and access points from the greater art world, while others wanted to be recognized by the art world and create a market for their work.

wwwwwwwww.jodi.org, Jodi.org (1995).

My boyfriend came back from the war, Olia Lialina (1996). Other versions.

Agatha Appears, Olia Lialina (1997).

Form Art, Alexei Shulgin (1997).

Link-X, Alexei Shulgin (1997).

_readme.html, Heath Bunting (1996).

The Great Wall of China, Simon Biggs (1996).

Hell.com, Kenneth Aronson (1995).

Darko Maver, 0100101110101101.org (1998).

King's Cross Phone In, Heath Bunting (1994).

The Web Stalker, I/O/D 4 (1997)

Every Icon, John Simon Jr. (1997)

Mouchette.org (1996).

Triggerhappy, Thomson and Craighead (1998).

Weightless, Thomson and Craighead (1998).

Now here/Nowhere, Bridhid Lowe (1998).

Cunnilingus in North Korea, Young Hae Industries (2001).

Zombie and Mummy, Olia Lialina (2002).

Clash with commercialism

With the evolution of Web 2.0 and web commerce, the look of the Internet changed dramatically, and corporate online presence led to increased ambiguity between commercial and artistic or editorial content. Some Internet artists created work that called attention to the changes and made work that critiqued online commerce and corporate presence, but the experimental and novel nature of Internet art was marginalized during this period.

Net art repositories

Throughout the history of Internet art, online repositories were founded to catalog art. Often the distinction between the works and the repositories themselves was blurred as in the case of "The Thing", which started as a BBS (bulletin board system) that predated the World Wide Web, later becoming a web repository of the work that was shared on the BBS and for new work.

adaweb was founded in 1994 by Benjamin Weil, as a platform for conversation and investigation into new forms of art making.

In 1995, the DIA Art Foundation founded DIA Web Artists, which served as a curatorial platform for online art.

Mark Tribe, an artists and curator in Berlin, founded Rhizome.org, an online platform and database of works that used digital media and new technologies generally, as well as Internet art.

In 2002, runme.org was established as a repository for software art, sharing many characteristics, technologies and platforms with earlier Internet artists .

Contemporary Internet art

The movement that compromised early Internet art and net.art faded into obscurity to some extent following the commercialization of the web, but many artists incorporate Internet based work in their practice to this day.

Why have there been no great net artists?

In 1999, Steve Dietz, a curator and "platform creator", publish the essay, "Why Have There Been No Great Net Artists?", taking it's title from the Linda Nochlin essay, "Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?", which argued that the role of women in social structures were responsible for repressing the emergence of great female artists. Dietz argues that the platforms for great art are not conducive to the work of Internet artists, which require the context of the Internet itself, much as film and literature occupy different platforms, so the idea that Internet artists should emerge the way artists in the past have is flawed.

There has been some institutional support of net art, but it has been inadequate for the most part and essentially pays lip service to the idea of Internet art, acknowledging its existence without having the proper understanding to support it.

Stolen Pieces, 0100101110101101.org (1995-97).

The World's First Collaborative Setence, Douglas Davis (1994).

Brandon, Shu Lea Cheang (1998).

Uncomfortable Proximity, Graham Harwood (2000).

Internet art creates an ambiguous market. Selling digital copies of work has always been difficult. One of the only unique things about a website is often its URL, which has by default become the easiest way to sell works of Internet art, but has not proven to be particularly viable for traditional collectors. Other models for commodification have been tested, but with no stand out successes.

Megatronix, Teo Spiller (1999).

While there has always been political art, much of Internet art is politically defined to the extent that it doesn't operate in the way that we are used to art working. These works blur the distinction of art and activism, much in the way that works from Dada and Fluxus did.

GW Bush website, RTMark (1999).

The Bomb Project, (2000-Present).

Dolores from 10 to 10, Coco Fusco (2002).

They Rule, Josh On and Future Farmers (2001).

Internet art simply has defied definition by the art world, favoring an anti-art and anti-commercial stance that it has adopted from Dada and Fluxus and other influences. Internet art works are often created in direct opposition to established art making practices, as we have seen in the examples of early Internet art, through work continuing to be made today.

Duchamp Sign, Vuk Cosic (1997). History of art for airports.

Resources

- Olga Goriunova -- Art Platforms and Cultural Production on the Internet

- Rachel Greene -- Internet Art

- Julian Stallabrass -- Internet Art: The Online Clash of Culture and Commerce

- Josephine Bosma -- Nettitudes

- John Ippolito -- Ten Myths of Internet Art

- In the Name of Art -- Ewan Morrison and Matthew Fuller